Accessibility links

Article continues below

It seemed as though the whole world had been buried in concrete. Perhaps it was jetlag, but the view was dizzying: the city, pouring away to the horizon in every direction. Shanghai is one of the world’s largest metropolises. From the viewing platform of the Shanghai Tower, the second tallest building in the world, it looked endless – a wave of skyscrapers rippling outwards, fading to a blue blur of residential blocks in the far distance.

The modern cityscape is as much geological as it is urban. If Shanghai is a concrete desert, New York is the original canyon city, its skyscraper-lined streets forming deep valleys of the kind that, in the past, only great rivers could create over thousands of years. In a late essay, Virginia Woolf pictured herself swooping like a bird over the Hudson estuary, past Staten Island and the Statue of Liberty to the concrete chasms of Manhattan. "The City of New York, over which I am hovering," she wrote in 1938, "looks as if it had been scraped and scrubbed only the night before. It has no houses. It is made of immensely high towers, each pierced by a million holes."

The first cities replicated the environments that once-nomadic people depended on, concentrating shelter and sustenance in one place. The metropolis of the present offers its inhabitants the whole planet in microcosm. As the author Gaia Vince writes, the buildings and infrastructure of the urban landscape simulate "the high view of mountains, the protection of dry caves, the fresh water of lakes and rivers".

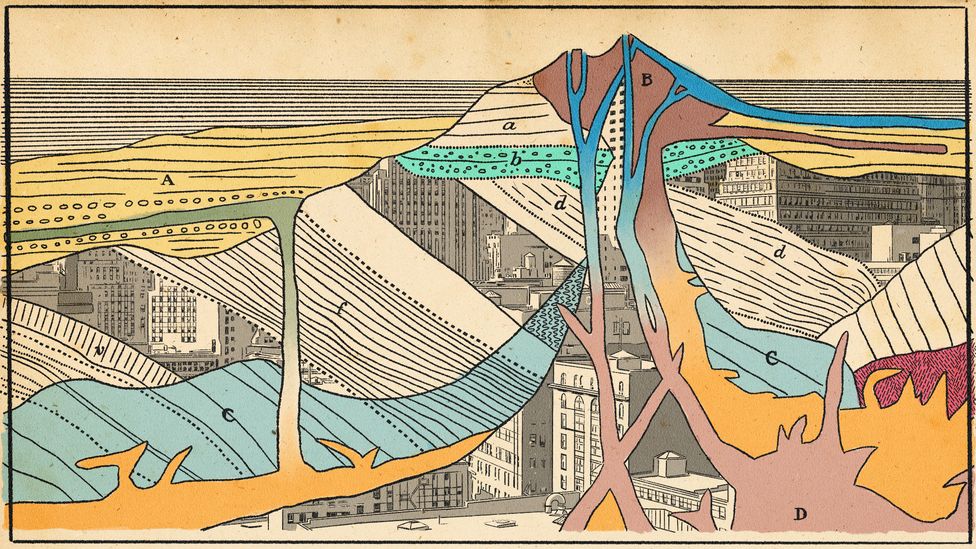

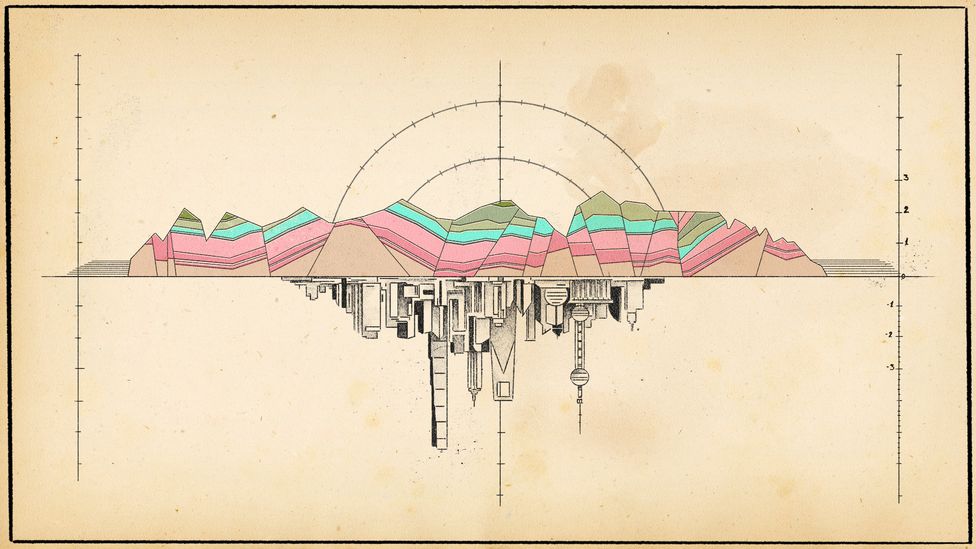

If cities have a geological character, it begs the question of what they will leave behind in the stratigraphy of the 21st Century. Fossils are a kind of planetary memory of the shapes the world once wore. Just as the landscapes of the deep past are not forgotten, how will the rock record of the deep future remember Shanghai, New York and other great cities?

You may also like:

- The guards caring for Chernobyl's abandoned dogs

- How to reboot civilisation

- How to build something that lasts 10,000 years

You might assume that cities are too ephemeral to leave behind a fossil. "Most buildings are designed to last for 60 years," says Roma Agrawal, structural engineer for the Shard skyscraper in London. "And I always thought, that feels really short, because that’s my lifetime." If you wanted to build something that would stand in tens of thousands of years, "then the forces that you need to contend with become huge", she explains. Most engineers don't look that far ahead.

With skyscrapers at its core, Shanghai's concrete desert stretches to the horizon (Credit: Emmanuel Lafont)

But while a building might not be designed to stand tall for millennia, that does not mean it will lack a geological legacy. According to Jan Zalasiewicz, emeritus professor of palaeobiology at the University of Leicester, it is "a quite reasonable, even prosaic, geological prediction" that a megacity will leave a fossil. I asked him how he could be so certain. "As a geologist, you’d almost put the question the other way around," he replied. "How can you prevent this?"

It’s a matter, he says, of durability, abundance, and location. The main components of a modern city have their origins in geology and are therefore, in their different ways, highly durable. The majority of the world’s iron ore formed nearly two billion years ago. The sand, gravel, and quartz in concrete are among the most resilient substances on Earth. These hard-wearing materials once existed in natural deposits. But where before it was only water, gravity, or tectonic activity that moved them, now it’s a combination of human initiative and hydrocarbon fuels.

Every 100 years, the mining and construction industries move enough rock around the planet to create a new mountain range

We live in the greatest age of city-building the world has ever seen. Three hundred years ago, there was only one city with a population of one million (Edo, modern-day Tokyo). Today there are more than 500, all of them dwarfed by megacities like Mexico City (population: 21 million), Shanghai (24 million), and Tokyo (now 37 million). As I discovered while researching my book Footprints: In Search of Future Fossils, the quantities of materials involved are staggering. Every 100 years, the mining and construction industries move enough rock around the planet to create a new mountain range, 40km wide, 100km long, and 4km high (25 x 62 x 2.5 miles). Enough concrete has been cast since World War Two to cover the entire planet, land and sea. According to a recent study in the journal Nature, there is now a greater mass of buildings and infrastructure on the planet (1,100 Gigatonnes) than trees and shrubs (900 Gigatonnes).

Location matters in determining the kind of fossil a city will leave. In geological terms, land is never static – either climbing or sinking on a "tectonic elevator". A city like Manchester in the UK, which is situated on ground still rising after the last ice age, will erode entirely over time, washing a trail of brick, concrete, and plastic particles out into the Irish Sea. "But many of the world’s largest cities are deeply anchored in the mouths of deltas and coastal plains," says Zalasiewicz. "And they’re subsiding. Deltas sink, that’s what deltas do." In many cases, human activity is massively hastening this process. Since 1900, Shanghai has sunk by 2.5m (8ft) due to groundwater extraction and the weight of its buildings pressing into marshy ground. Added to which is sea level rise, which could exceed a metre by 2100. "But even without sea level rise," says Zalasiewicz, "it would be inexorable, because the subsidence is steady."

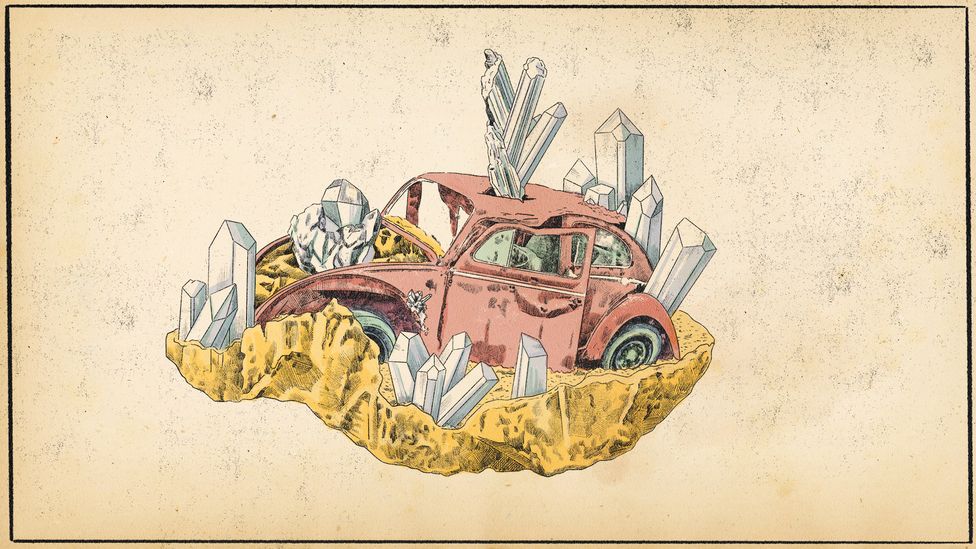

From plastic to glass, a city's components are geological in nature, and much will be preserved (Credit: Emmanuel Lafont)

What about a particular structure? Shanghai Tower weighs 850,000 tonnes: a 632m-tall (2,073ft) steel framework with more than 20,000 panes of glass, and 60,000 cubic metres (2.1 million cubic feet) of concrete. How will it fossilise?

"Let’s say Shanghai will behave as Amsterdam and parts of the Mississippi delta are behaving now, where sediment is pouring in," says Zalasiewicz. "You will get progressive changes over thousands and hundreds of thousands, and millions and then tens of millions of years."

Like other wealthy cities, Shanghai will be vigorously defended against sea level rise, but climate feedback loops mean that the oceans will creep upwards for centuries to come. When the water does become unmanageable, there will likely be a slow abandonment, with the wealthiest leaving first. Poorer people, with nowhere to go, may have to adapt to semi-submerged conditions. Over several hundred years, the upper levels of Shanghai Tower will decay as wind and water erode them. Perhaps they’ll be weakened, too, by scavengers harvesting valuable materials. If the lowest levels have managed to remain above water, only the bottom one or two storeys will remain standing, surrounded by a rubble layer of fallen debris.

The inevitable inundation may come from the sea, or from the collapse of the massive Three Gorges Dam higher up the Yangtze river. But as it floods, the water will bring vast amounts of mud and sediment that will cover the ground floor and subsurface levels like a wax seal. After 500 years, only a low-lying island would remain where the tower once stood, streaked red by oxidised iron left over from the four immense steel supercolumns that once held it in place. The real story will be below ground.

Many human-made objects – the paraphernalia of a city – will endure (Credit: Emmanuel Lafont)

Shanghai Tower has five subsurface levels, including shops and restaurants and parking space for 1,800 vehicles. Entombed in thick mud, these spaces will be preserved against erosion and begin to fossilise – "the Pompeii effect, if you like," says Zalasiewicz.

Almost immediately, water making its way down to the lowest levels it will react with the calcareous material in concrete, to form cathelmites – stalactite- and stalagmite-like growths that form in human-made environments. These will continue to grow for thousands of years, transforming the shopping mall into something akin to a horror movie set. If humanity is still around, most things of value will have been stripped out before the Tower is completely abandoned, but perhaps not everything. Aluminium in the ventilation system, stainless steel in the food court – maybe even a few cars in the garage levels will be left to perform remarkable transformations.

At first the car will simply rust but, as iron dissolves well in anoxic water, once the oxygen level decreases its metal components will begin to dissolve. Or perhaps a part of the chassis will mineralise, reacting with sulphides to form pyrite. The iron in steel beams or embedded in reinforced concrete, kitchen implements, or even tiny quantities of iron in the speaker of a mobile phone will all acquire a glittering sheen. Even whole rooms – a food court kitchen fitted with stainless steel worktops – might be transformed into fool’s gold.

Plastics, protected from the harsh effects of weathering and UV light, will be among the most patient materials. "No one knows exactly how long they will last," says Zalasiewicz, "but an analogy might be drawn with another long-chained polymer." If a bug happens to become stuck in some melted plastic before the Tower is sealed off, it may be preserved like the insect in amber in Jurassic Park.

Over time, the plastic will carbonise and become brittle. Sheets of aluminium in heating ducts will link up with silicates and slowly change into China clay, providing a perfect environment for fossilisation. One hundred thousand years after the tower was abandoned, the clay will have hardened into shale studded with the ghostly impression of plastic knife handles, light switches, or the knob of a gear stick.

What will our descendants make of the glass screens and rare earth metals of our smartphones? (Credit: Emmanuel Lafont)

The story continues even deeper underground. The entire Shanghai Tower sits on top of a concrete raft, one metre thick and covering nearly 9,000 sq m (97,000 sq ft). Beneath this are 955 concrete-and-steel piles, each a metre in diameter, driven up to 86m (282ft) deep into soft ground. After several million years, as the weight of the sea water and sediment warps the subterranean layers beyond recognition, some of the foundation piles will fracture, twisting within compacting mudrock formations like the fossil roots of an immense, long-vanished tree.

As millions of years stretch into tens of millions, the transformations come more slowly. Rare earth minerals, leached from discarded mobile phones and other electronic devices, may begin to form secondary mineral crystals. Glass from windshields and shop windows will devitrify, darkening just as obsidian does after long burial. By now, the entire city is compressed to a layer perhaps only a few metres thick in the strata. All that is left of Shanghai Tower is a geological anomaly studded with the fossil outlines of chopsticks, chairs, sim cards, and hair clips.

All of this will be deeply buried, in some cases thousands of metres down. But geology never stands still. After around one hundred million years, as new mountain ranges begin to form, the layer of compacted rubble that was once Shanghai Tower may be pushed upwards, and revealed.

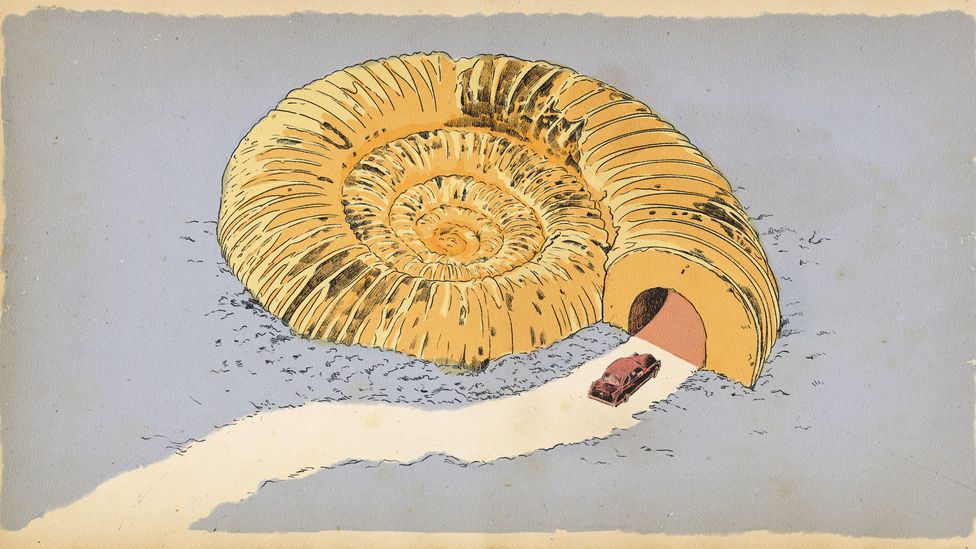

Our fossils will tell the story of how we got around (Credit: Emmanuel Lafont)

"Structures have stories," writes Roma Agrawal in her book Built. They tell the stories of the people who lived in them and the world they were made for. The same goes for the remains of Shanghai Tower, even after such so much time has passed. Any future explorers, whether an evolved form of life on this planet or from another world, would be able to recreate a picture of 21st Century life in astonishing detail, provided they can use the same techniques that geologists use today.

Fossilised bicycles or rubber boots will indicate we were bipedal, a fossil keyboard will suggest the shape of our hands, and spectacles or hearing aids will disclose how we perceived the world. The outline of a set of dentures, a motorcycle helmet, a wheelchair, a neoprene wetsuit or even a shop mannequin, will recall the contours of our bodies, perhaps even that we were sexually dimorphic.

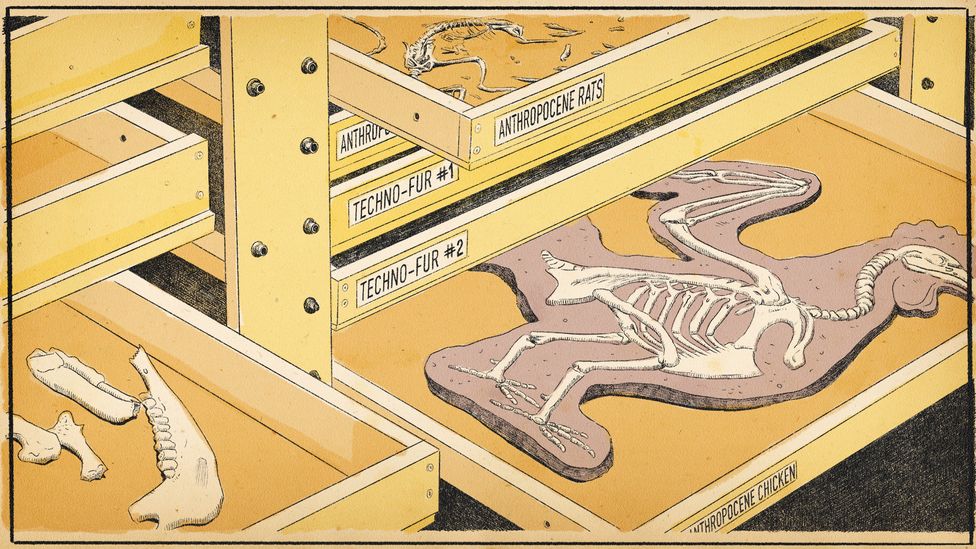

Archaeologically-speaking, clothes have not been very hard-wearing for much of human history, says Zalasiewicz. "But as soon as plastic came along, we suddenly have super durable techno-fur, as it were – detachable techno-fur."

It isn’t just our bodies that will be remembered: our minds will leave a trace as well. The scale and complexity of our fossil cities will testify that we were social beings. Perhaps a deep-future geologist might conclude we were a hive species like termites, but it’s likely that there will be enough evidence of individual invention in the sheer variety of fossil imprints, what Zalasiewicz calls "technofossils," to suggest otherwise. Moreover, the ingenuity needed to create something like a mobile phone – extracting deeply-buried hydrocarbons and metals, then transporting them between continents to be manipulated and combined in highly complex assemblages – will record the scale of our invention.

Will the animals of the Anthropocene and "techno-fur" define our time? (Credit: Emmanuel Lafont)

Like the fossilised burrows and tracks left by ancient creatures, our trace fossils will show how we moved. But they’ll also record that we didn’t only depend on our own locomotion. There are more than 300km (186 miles) of subway line beneath Shanghai. Protected against erosion, it’s possible that whole lengths of track may be preserved, even a train carriage. Preserved lengths of road tunnels – complete with kerb stones, ventilation systems, and the glass and copper wiring of electric lighting – will hint at the 50 million km-long (31 million mile) network that once wrapped around the planet. Thick deposits of clinker in the harbours of major port cities, dumped overboard by coal-powered steam ships in the 19th Century, will be read like nodes in a map of global seafaring.

The fossil remains of Shanghai Tower could be matched to the remnants of other tall buildings in other cities, to form a portrait of a global culture of city dwellers who built with the same synthetic materials and used many of the same objects day-to-day. This homogeneity would also express itself in future palaeobiology. Fossils of the same handful of species will turn up again and again on every continent other than Antarctica. The "Anthropocene rat" will be a signature species of the great age of city-building. Mixed with the rubble and plastic in landfill sites across the world will be the bones of some of the 60 billion chickens killed for human consumption each year.

In fact, it’s likely that landfill, rather than the remains of cities themselves, will tell the most richly-detailed stories. Modern landfill sites can build up thicknesses of several tens of metres and cover many square kilometres. Lined with durable neoprene, they are filled with individual plastic bags full of waste, creating a double seal against the corrosive influence of UV light, oxygen, water, and chemical leachates. For each relic city there will be a shadow city, vast fossil middens punctuated with the outlines of all that we discarded.

Even the grandest city has no power against nature and time (Credit: Emmanuel Lafont)

The future rock record will testify that not all of us had the same impact – that those settled near sites of extraction lived far less fossil fuel-intensive lives than those in cities. Future fossils will hint at this tale of global inequality. They may also tell of the impact we had on generations yet to be born, who were forced to live with the consequences of our carbon addiction.

Of course, there may be no-one to find or make sense of what is left of our cities. But that doesn't mean that we should not seek to imagine the long-term legacies we are leaving behind. We might all do well to think more like geologists. The earth scientist Marcia Bjornerud calls for the cultivation of "timefulness", which she describes as "a feeling for distances and proximities in the geography of deep time". Her approach encourages us to think more timefully about the scale of our impact on the planet, and consider what story we want our future fossils to tell.

After visiting Shanghai Tower, I took a train to Nanhui, a new city built on the Pudong coast to accommodate Shanghai’s over-spilling population. The tide was out when I arrived on the beach. At my back, a wall just taller than me, curving like a cresting wave, faced out to sea. Shanghai has constructed 520km (323 miles) of these sea barriers, but the ocean will take the city eventually. Whether in 100 or 10,000 years from now, what once was one of the world’s greatest cities will begin a slow transformation into geology. "Let me show you the tide / that comes for us," write Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner and Aka Niviâna in their poem Rise, "forcing us to imagine / turning ourselves into stone."

* David Farrier is a professor of literature and the environment at the University of Edinburgh. This article is adapted from his book "Footprints: In Search of Future Fossils", which is available in the US and the UK.

--

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

No comments:

Post a Comment